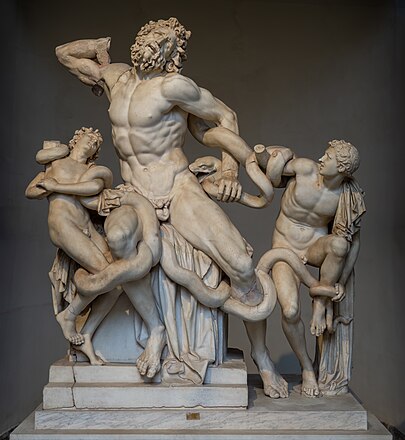

There’s a famous story about how, in 1506, an ancient statue called the Laocoon was discovered buried in an Italian vineyard. If you’re trying to picture what it looks like, it’s a man named Laocoon flanked by his two sons as they’re being dragged into the sea by serpents to prevent them from exposing the trickery of the Trojan horse at Troy. The statue was had already garnered fame and achieved mythical status because the Roman historian Pliny had described it over a thousand years prior as the best statue ever carved by a Greek. So people knew that it existed but it had long been lost.

Pope Julius II, on hearing about the discovery, immediately sent his favorite sculptor to look at the statue and acquire it for the Church (all the best art belongs to us!). That sculptor he sent was Michelangelo, and the only flaw in the statue was a missing right arm on Laocoon himself. Most renaissance sculptors argued that the missing right arm ought to be restored held out in a heroic gesture. Michelangelo disagreed. In looking at the musculature on the upper arm, he was quite confident that the forearm was bent back. He lost the debate, though, and the restored arm was held out straight. Then, 400 years later in 1906, the original missing arm was discovered. It was bent back, just like Michelangelo had said. He was a master of the human form to the extent that, for him, the invisible and the visible were seamlessly interlinked.

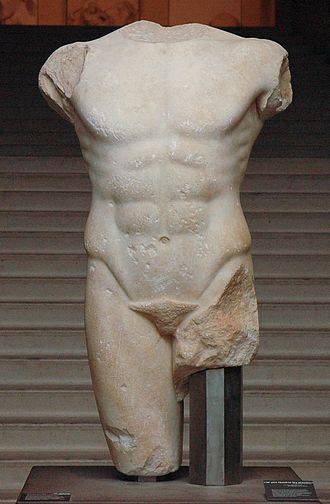

Maybe you’ve been to a museum and looked at ancient Greek statuary. Often, significant pieces of the art are damaged – missing fingers, limbs, even the head vanished forever. There’s still a fragile beauty that exudes from those expressions of sensible love created by ancient artists, and to me at least, the rooms of ancient Greek sculpture at the museum are far more affecting than the rooms full of modern art.

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke describes the experience of being in a museum and meditating on a broken statue. He calls it the, “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” The statue is missing its head and all four limbs. Missing, writes Rilke, those divine “eyes like ripening fruit.” You might think that a statue with no head or face, that is missing so much, would lose its luster, and yet the marble torso is “suffused with brilliance from inside, like a lamp.” There is grace in the curve of the chest, and the torso seems to smile and maintain virility with those shoulders that are a translucent cascade of living stone. I wonder how long Rilke stays quiet sitting in that room with that statue until, suddenly, from all its borders beauty bursts forth like a star. Even though the statue has no physical eyes, as he looks at it, it begins to look back at him. It sees him. And then, having made a deep connection with transcendent beauty, the poet almost with a sigh and renewed purpose, ends his poem with a very simple, sacred mission, “You must change your life.”

Why? Because he has seen the unseen. The invisible has peered at him, known him, and loved him. When this happens to us, when we glimpse the beauty of the world beyond this one, what can we do but give ourselves to this transcendent love? Bend our heart and will entirely to the pursuit of this love?

Christ is the invisible made visible. As St. Paul says, “Who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature.” You might be thinking of the line from the Creed right now; “factórem cæli et terræ, visibílium ómnium et invisibílium.” He is Lord of all, the visible and invisible, and in him the two realms are overlapping bodies. The spiritual and physical are intertwined in a primordial unity such that we might find it impossible to distinguish the giver from the gift.

This is because the gift is making us like the giver, the visible drawing us into the invisible, earth is a ladder to Heaven. What Christ makes visible is the blueprint for what we are becoming. We take on his heft and line, shape and stature. What Christ is we are adopted into through grace.

Here’s the collect we prayed this morning; “Deus, qui diligéntibus te bona invisibília præparásti.” This is in reference to the invisible goodness that God is preparing for us. Going on; “infúnde córdibus nostris tui amóris afféctum.” Pour your love into our hearts. With that word “affectum,” we might say pour a burning love into our heart, a love that reaches all the way to the “affect,” a deeply rooted fundamental change, a firmly held disposition that shapes and guides us going forward.

The collect, like all of the collects of the Roman Rite, is a marvel of poetic economy. It’s packed with words of romance, love reaching out to God, a striving to make a connection of the heart. This invisible connection leads to the virtue of hope that we might attain his promises. The unseen will be seen. How? Through a building up of love.

We are asking God to reveal to us the hidden grace that lights up the entirety of the picture. Who we are, why we were made, and to where we are going. Our own unaided eyesight only extends so far. Our own ability to love is limited and flawed. So we are asking God to see us, to know us, and to assist us in building up divine love in this world so as to bring it ever closer to his Sacred Heart. We are asking God to lift us up into perfect love, which is a love personified in the concrete, sensible, very real and very visible love of Christ. This is how the affect of the heart is shifted, by which I mean this is how we are transformed and begin to look like that which we strive for in hope. We become, in our own humble way, a picture of Christ.

“Hallow Christ in your hearts,” urges St. Peter. You are part of the process of redemption. You are like a sacred artist meant to adorn your life with beauty and love and goodness. This is, of course, for our happiness, because what could possibly be better than to live in the manner God has set out for us, but it’s also for the sake of the Kingdom and for the sake of the lost, because God’s grace is luminous within you when you cooperate with him. So perhaps it’s more accurate to say that God is the artist and we are his, as yet, incomplete works. Pray that his work will be completed within us and that our lives become bright with the radiance of his love.